Shorter Development Cycles, Longer Holds

Real estate development cycles are shorter than ever today, meaning the best investments are those where developers and owners can hold on for the long haul. AECOM Capital CEO John Livingston discusses.

Transcript Download Transcript

Shorter Development Cycles, Longer Holds

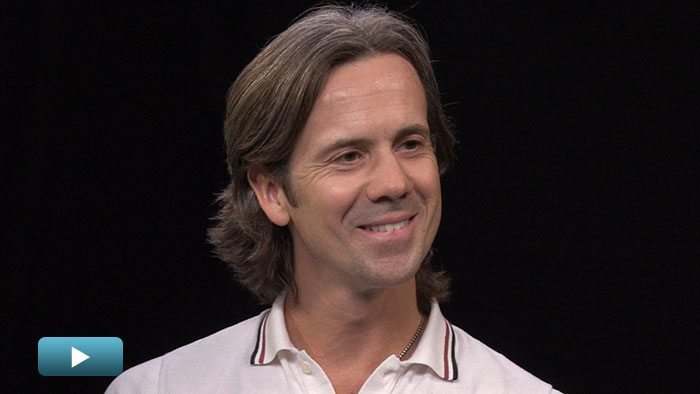

With John Livingston of AECOM Capital

Zoe Hughes, PrivcapRE: I’m joined here today by John Livingston, Chief Executive of AECOM Capital. John, thank you so much for joining us today.

John Livingston, AECOM Capital: Thanks for having me.

Hughes: John, you’ve lived and breathed plenty of development projects and real estate cycles over your career. You’re Chief Executive of the investment arm of AECOM and former president of Tishman Construction Corporation. I’m really keen to get a sense—as you look to invest as a co-GP in development projects across the U.S.—as to how you view the risks within commercial real estate market, particularly in the development cycle. First and foremost, though, give me an idea as to what’s your strategy today?

Livingston: Our strategy is to invest in gateway cities across the U.S. where Tishman’s…subsidiary, Hunt Construction, has a presence. That means Boston to Miami, Chicago, San Diego to Seattle, Texas and Denver. Gateway cities—because you buy in at a higher price, but there’s more growth—and not secondary and tertiary cities. We look across asset classes. Today, it’s mostly multifamily, some condo. We’re not afraid of hotels and we think generally New York and San Francisco may be in the fifth inning, but the other cities are probably in the third inning. So, I think we’re smack dab in the development cycle. But, having said that, when I was a young man, cycles were 10 to 15 years—they’re now five to seven years.

Hughes: Much, much shorter cycles then.

Livingston: They [were] much shorter because of the transparency in the marketplace. Things move so much quicker because of the internet.

Hughes: How many projects have you actually done to date for AECOM?

Livingston: We started AECOM Capital in January of 2013. We’ve committed to 14 projects and it totals about $3 billion in development.

Hughes: Where do you see the development cycle? I get a sense from you that perhaps it’s more slight pockets of overdevelopment. You’re actually not too concerned about general oversupply in the market.

Livingston: Historically, you make money in real estate by holding on. If you’re a small company and times get bad or there’s a recession, you give the keys back. If you’re a stronger, more financially-based company, you can hold on during the downturn. My view is old school. You invest in development—good locations with good partners—and good real estate projects and [you] hope they’re great one day and in good cities. There’s nothing more than that. There’s always a question of oversupply, but you have to take a longer-term view. It’s the bankers of the world that told us we have to take a short-term view, but that isn’t really the case in real estate. It’s really a longer-term view.

Hughes: If the development cycle is so much shorter today, how does that impact your view of the market as we currently look?

Livingston: It depends on the location. As I said, in New York and San Francisco, which are the two hottest markets in the country, land prices are peaking. It’s beyond what you can imagine where they ever were in my lifetime. We know the cost of construction and the financing rates generally. We know the market rates generally. The only real variable is land, so you can’t overpay for land for development. I look in those markets and improving locations, transforming neighborhoods, where the land price is still reasonable. Then, you build for the long haul. You just have to accept the cycles.

Hughes: I know two big projects you’re doing at the minute: one is called Flushing Commons in Flushing, Queens, New York. This is a five-acre, $1-billion multifamily project. Talk me through that. What were some of the drivers behind that?

Livingston: That project was a parcel of land (a garage) owned by the City of New York. They put it out to RFP three times in the last 25 years. Finally, as these folks wanted, about 10 years ago, we came along a couple of years ago and bought into it. That’s a project that will transform that neighborhood. It’s a $1.2-billion project. It’s about 1 million square feet overall, I think.

We’re only doing the first phase, which is 150 apartments and 75 office condos, and some retail and parking. But I like the idea of being in a neighborhood that’s transforming. What people don’t know about Flushing (maybe some do) is that it has the greatest density of Chinese and Koreans in New York and probably the country. It’s the third busiest subway stop as well. People want to be there and it’s the first stop for many Asians who come from overseas. And you can buy a condo there for one-half to one-third the price of Manhattan.

Hughes: Have you seen that slight overdevelopment in terms of multifamily? Because, obviously…when we talk about potential oversupply or potential overdevelopment, multifamily is always the property type that’s picked up first. Are you beginning to see that real growth in development projects in multifamily across New York?

Livingston: In New York, the thing is, every piece of land is priced for condo, not for rental. People would love to build rental. There’s an enormous demand because rental occupancy is 99.5% or something and rental rates have gone through the roof. But you can’t afford to buy the land. It doesn’t support rental. The new normal is $800 to $1,000 per buildable square foot. So, you’ve got to sell condos for $3,000 or more to make it work. So, you can forget rental in New York, in my opinion, unless you’ve owned the land for 100 years and it’s really cheap and you want to do rental.

In other markets, land is much cheaper. We bought six acres of land in downtown Los Angeles at $45,000 a door. It’s now valued at twice that, so we got in at the right time.

Hughes: This is one that you’re actually doing with Mack Real Estate and Capri Capital.

Livingston: That’s right. There are five separate sites, six acres three or four blocks from the Staples Arena. It’s going to hold about 1,400 rental apartment units and a 200-unit hotel. But, as I said, five separate sites. The first one is a 362-unit, stick-built project with Capri and Mack as the lead developer.

Hughes: Talk to me about some of the risks you’re willing to take. You’re willing to take some entitlement risk—how much?

Livingston: We come in as a co-GP. We are not the day-to-day developer. As I say, the developer is driving the bus. I’m riding shotgun. We’re a sidecar. We will come in early and take GNP risk because our construction company, Tishman, will build it. I’m familiar with that and we’ll take that kind of risk. And we’ll take some entitlement risk. We won’t take the five-year kind. I’m too old. We’ll take the 12-month entitlement risk that mostly is administrative. I’ve got to see an end to the process, and typically there’s gold at the end of the rainbow. But some developers spend five to 10 years doing these things.

We bought a piece of land in L.A., on Sunset Boulevard. The operating partner bought it eight years ago and spent six years entitling it painfully. We came in two years ago and bought half the property with them. So, we got the benefit of all his hard work. I don’t have the resources to go through a painful, six-year process—a very expensive process.

Hughes: Where do you see us in this cycle? I’d love to point out the fact [that in] your career, 35 years, you’ve built some fantastic projects: One World Trade Center, Javits Center, you’ve done the restoration of New York Plaza, the City Center in Las Vegas—18 million square foot. There’ve been some major projects you’ve been involved in. What are the key lessons you’ve learned and where are we today?

Livingston: A lot of very smart people have built into the wrong market, that’s for sure. And there’s been problems, so there’s no answer to all this. Like I said earlier, in a perfect world you want to build into a down market. You just don’t want to believe your own stuff. You want to make sure you’ve done your homework and you’ve checked what’s in the ground. You’ve done everything you’re supposed to do to build properly.

As I said, I think that New York and San Francisco are probably past the halfway mark. I think other major cities—L.A., Chicago, Boston, D.C., Denver, Dallas, whatever—are on this side of the 50-yard line. I think there’s still some real runway with those other cities. Here it’s going to be tough to build something in San Francisco to make sense. And people are banking on the next wave of investors. Now, it’s the Asians. It was the Japanese, before that it was the Germans, the Brazilians, the Russians. Every five or 10 years, it’s a new group from overseas that bails people out. Right now, the Asians are here and the Chinese in a very big way.

I teach and I always say that at a 4% cap rate and 4% debt rate, most everything works. Twenty years ago, I would never have developed if the return on cost was 6%, but that’s what it is today. As long as you have 150 basis–point spread between what you can build it for and what you can sell it for, you can get financing in the right markets.

Hughes: You mentioned the fact that real estate, particularly development cycles are obviously shorter owing to the transparency in data that we have in the industry. One interesting comment that Bill Wheaton made at a talk recently was that given that transparency and that data, have we actually tamed development cycles?

Livingston: That would be lovely. If that was the case, we could hire junior people to do everything and I don’t think so at all. I think we have tremendous transparency in the marketplace and tremendous data, but developers take risk. Some are contrarians and some say you can show me that there’s 10,000 units coming online in downtown L.A., but I still think there’s a wider market and I build longer term. So I don’t think development is a science. I think it’s an art.